This year, to mix things up a bit, I will start with composers and musicians born in 1916 and go back in time. We'll see where it leads.

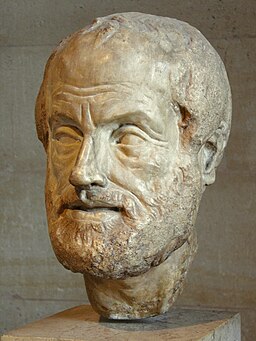

But first, let's celebrate the 2,400th anniversary of Aristotle, the ancient Greek philosopher, scientist, student of Plato and tutor of Alexander the Great. Thomas Aquinas in the Middle Ages simply called him 'The Philosopher.'

Aristotle covered a wide array of subjects which together form the first comprehensive system of Western philosophy. He wrote--judging by today's philosophical endeavors--in a plain and accessible language.

Music and music education are covered in his books on Practical Philosophy, chiefly in Politics and Poetics. Music can be either for amusement and relaxation during leisure time or conduce to virtue. Aristotle recognized music's ethical and emotional power--expressed through the Greek modes, their 'harmony,' and rhythm. (2) He described the imitative and cathartic functions of Greek tragedy--of which the chorus was an integral part ,(3) and wrote about the value of teaching music to young boys--age 5-7 to puberty, i.e. the second stage of life. (4)(5) The latter, however, comes with some caveats, for example:

- One should teach music enough to build appreciation in the listener, but not to the extent that it turns the young charges into professional musicians. That task, after all, belongs to the lower class.

- One should not teach music that excites too much. Instrumental music, especially flute-playing, tends to have this effect on young people.

That music was part and parcel of Aristotle's world, becomes clear not only from Politics and Poetics, but also from the many examples and concepts of music, musicality, sound, voice, etc. in his other treatises. A few examples:

In Prior Analytics Aristotle explains that character can be inferred from features, since passions and desires, i.e. 'natural' emotions, change body and soul together. Learning music, although it has some effect on the soul, cannot be called a 'natural' affection. (6)

In Posterior Analytics the Philosopher explains that the better the evidence the sounder the logical proof.

In Physics when describing ancient thinkers' ideas about masses, elements and principles, Aristotle asserts that:

Later in the same treatise he considers 'sense,' and explains that 'concord' of the actuality of the sensible object (e.g. 'sounding') and of the sensitive faculty (e.g. 'hearing') always implies a 'ratio' (e.g. 'hearing and 'what is heard') and claims:

- That the 'one,' i.e. the measure or unit, is indivisible and not the same in all classes, that the 'measure is not always one number,' and that in every category we must 'ask what the one is, as we must ask what the existent is.'

- He cautions against believing that 'number' causes a thing to exist or that numerical analogies are anything more than pure coincidence.

Let's now jump all the way to 1916 and discover Jan Hakan Aberg (1916 - 2012), first up in our list of 100-year anniversaries.

Aberg was a Swedish organist and composer active at Härnösand Cathedral.

He is represented in the current Swedish Book of Psalms (1986) with two songs, In dulci jubilo and Så älskade Gud världen all.

Here is an arrangement by Aberg of the psalm I himmelen, i himmelen (In Heav’n above) which was probably written in 1620 by Laurentius Laurinus. A serene start for the New Year.

_______________________________________________________________________________

(1) After Lysippos [CC BY-SA 2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons.

(2) David Binning Monro, "The Modes of Ancient Greek Music, I. Introductory." Oxford University, Clarendon Press, 1894, p. 1. (https://books.google.com/books?id=jmwpAAAAYAAJ&ots=bipnN551SQ&dq=greek%20modes%20and%20emotions&lr&pg=PA1#v=onepage&q=greek%20modes%20and%20emotions&f=false (01/09/2016))

(3) Golden, Leon. “Mimesis and Katharsis”. Classical Philology 64.3 (1969): 145–153. (http://www.jstor.org/stable/268156 (01/09/2016))

(4) Aristotle, "Politics."Politics, Book VIII, Chap. 5-7. (http://faculty.smu.edu/jkazez/mol09/AristotleOnMusic.htm (01/09/2016))

(5) For Aristotle's views on women, see here.

(6) Aristotle, "Prior Analytics." Bk. II: Ch. 27, 70b, 7, translation Richard McKeon, "The Basic Works of Aristotle," New York, Random House, 1941, p. 106.

(7) Aristotle, "Posterior Analytics." Bk. I: Ch. 24, 85a, 22, translation Richard McKeon, "The Basic Works of Aristotle," New York, Random House, 1941, p. 147. Coriscus was also a student of Plato and a lifelong friend of Aristotle. Whether all the attributes applied to Coriscus by Aristotle were true, is unsure.

(8) Aristotle, "Topics." Bk. I: Ch. 15, 106a-107b, translation Richard McKeon, "The Basic Works of Aristotle," New York, Random House, 1941, pp. 200-204.

(9) Aristotle, "Physics." Bk. I: Ch. 2, 185b, 32, translation Richard McKeon, "The Basic Works of Aristotle," New York, Random House, 1941, p. 221.

(10)Ib., Bk. I: Ch.5, 188a, 35, p. 227.

(11)Ib., Bk. IV: Ch.7, 214a, 7, p. 281.

(12)Ib., Bk. VII: Ch.4, 248b, 9, p. 349.

(13) Aristotle, "On the Soul." Bk. II: Ch. 8, 419b, 3, translation Richard McKeon, "The Basic Works of Aristotle," New York, Random House, 1941, pp. 570-573.

(14)Ib., Bk. III: Ch. 2, 426a, 27, pp. 583-584.

(15) Aristotle, "Metaphysics." Translation Richard McKeon, "The Basic Works of Aristotle," New York, Random House, 1941, p. 681.

(16) Aristotle, "Metaphysics." Bk. IV: Ch. 5, 1010b, 8, translation Richard McKeon, "The Basic Works of Aristotle," New York, Random House, 1941, p. 746.

(17)Ib., Bk. X: Ch. 1, 1053a, 13, p. 836.

(18)Ib., Bk. V: Ch. 6, 1016a, 18, p. 759.

(19)Ib., Bk. X: Ch. 1, 1053a, 14, p. 837. The numerical ratio here may be for example determined by 'string-length.'

(20)Ib., Bk. X: Ch. 2, 1053b, 34, p. 838.

(21)Ib., Bk. V: Ch. 12, 1019b, 13, p. 766.

(22)Ib., Bk. V: Ch. 16, 1021b, 13, p. 770.

(23)Ib., Bk. V: Ch. 27, 1024a, 11, p. 775.

(24)Ib., Bk. IX: Ch. 8, 1049b, 29, p. 829.

(25)Ib., Bk. XIV: Ch. 2, 1089b, 20, p. 918.

(26)Ib., Bk. XIV: Ch. 5, 1093a, 12, pp. 924-925.

(27) Aristotle, "Ethics." Bk. I: Ch. 7, 1097a, 24, translation Richard McKeon, "The Basic Works of Aristotle," New York, Random House, 1941, p. 941.

(28)Ib., Bk. I: Ch. 7, 1097b, 24, p. 942.

(29) Ib., Bk. I: Ch. 7, 1098a, 7, p. 943.

(30) Ib., Bk. II: Ch. 1, 1103a, 32, p. 952.

(31) Ib., Bk. IX: Ch. 1, 1164a, 15, p. 1077.

(32) Ib., Bk. X: Ch. 3, 1173b, 28, p. 1097.

(33) Ib., Bk. X: Ch. 4, 1175a, 10, p. 1100.

(34) Ib., Bk. X: Ch. 5, 1175a, 29, p. 1100.

(35) Ib., Bk. X: Ch. 5, 1175b, 1, p. 1100.

(36) The work was found by French archaeologists in 1893, inscribed on a wall of the Athenian Treasury building in Delphi.

(37) Henrik Sendelbach [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.

|

| Aristotle (1) |

Aristotle covered a wide array of subjects which together form the first comprehensive system of Western philosophy. He wrote--judging by today's philosophical endeavors--in a plain and accessible language.

Music and music education are covered in his books on Practical Philosophy, chiefly in Politics and Poetics. Music can be either for amusement and relaxation during leisure time or conduce to virtue. Aristotle recognized music's ethical and emotional power--expressed through the Greek modes, their 'harmony,' and rhythm. (2) He described the imitative and cathartic functions of Greek tragedy--of which the chorus was an integral part ,(3) and wrote about the value of teaching music to young boys--age 5-7 to puberty, i.e. the second stage of life. (4)(5) The latter, however, comes with some caveats, for example:

- One should teach music enough to build appreciation in the listener, but not to the extent that it turns the young charges into professional musicians. That task, after all, belongs to the lower class.

- One should not teach music that excites too much. Instrumental music, especially flute-playing, tends to have this effect on young people.

That music was part and parcel of Aristotle's world, becomes clear not only from Politics and Poetics, but also from the many examples and concepts of music, musicality, sound, voice, etc. in his other treatises. A few examples:

In Prior Analytics Aristotle explains that character can be inferred from features, since passions and desires, i.e. 'natural' emotions, change body and soul together. Learning music, although it has some effect on the soul, cannot be called a 'natural' affection. (6)

In Posterior Analytics the Philosopher explains that the better the evidence the sounder the logical proof.

e.g. we know Coriscus the musician better when we know that Coriscus is musical than when we know only that man is musical...(7)In Topics, when discussing specific and ambiguous meanings of terms, he compares the meaning of the terms 'clear,''obscure,' and 'harsh' in sounds and in colors, the terms 'sharps' and 'flats' in music and in solid edges, the combined terms 'clear body' (meaning 'white') with 'clear note' (meaning a note easy to hear), 'sharp flavor' with 'sharp note', and 'color in bodies' with 'color in melodies.'(8)

In Physics when describing ancient thinkers' ideas about masses, elements and principles, Aristotle asserts that:

What 'is' may be many either in definition (for example 'to be white' is one thing, 'to be musical' another, yet the same thing may be both, so the one is many) or by division, as the whole and its parts.(9)Again in Physics when explaining principles and their contraries, and the presupposition that 'in nature nothing acts on, or is acted on by, any other thing at random, nor may anything come from anything else, unless we mean that it does so in virtue of a concomitant attribute,' he argues:

For how could 'white' come from 'musical', unless 'musical' happened to be an attribute of the not-white or of the black? No, 'white' comes from 'not-white'--and not from any'not-white', but from black or some intermediate color. Similarly, 'musical' comes to be from 'not-musical', but not from any thing other than musical, but from 'unmusical' or any intermediate state there may be.(10)Later in Physics in Book IV when discussing the meaning of 'void,' he asks the question:

But at all events we observe then that in one way the void is described as what is not full of body perceptible to touch; and what has heaviness and lightness is perceptible to touch. So we would raise the question: what would they [people] say of an interval that has color or sound--is it void or not? Clearly they would reply that if it could receive what is tangible it was void, and if not, not.(11)On 'commensurability' of motions and velocity in a circumference and a straight line (Physics, Book VII), Aristotle asks;

But may we say that things are not always commensurable 'if the same terms are applied to them without equivocation? e.g. a pen, a wine, and the highest note in a scale are not commensurable: we cannot say whether any one of them is sharper than any other: ... it is only equivocally that the same term 'sharp' is applied to them: whereas the highest note in a scale is commensurable with the leading-note, because the term 'sharp' has the same meaning as applied to both. (12)Aristotle addresses 'sound,''hearing,' and 'voice' in On the Soul. He explains that certain things 'have no sound,' such as a sponge or wool and that smooth and solid surfaces, like bronze, generate sound upon impact; that hollow objects reverberate, that sound travels both in air and in water, and that it is probable that 'in all generation of sound echo takes place.' He attributes hearing to the concurrent movement of air (or water) outside--caused by that which produces sound--and air inside the ear chamber. Voice is the impact of the inbreathed air against the 'windpipe' (the organ related to the lungs); the agent that produces the impact is the soul resident in these parts of the body; voice is sound with a meaning. (13)

Later in the same treatise he considers 'sense,' and explains that 'concord' of the actuality of the sensible object (e.g. 'sounding') and of the sensitive faculty (e.g. 'hearing') always implies a 'ratio' (e.g. 'hearing and 'what is heard') and claims:

'That is why the excess of either the sharp or the flat destroys the hearing,' .... and 'That is why the objects of sense are (1) pleasant when the sensible extremes such as acid or sweet or salt being pure and unmixed are brought into the proper ratio; then they are pleasant; and in general what is blended is more pleasant than the sharp or the flat alone...; while (2) in excess the sensible extremes are painful or destructive.Throughout Metaphysics Aristotle uses examples from the world of music, sometimes involving his old friend Coriscus and Socrates. 'The man is musical,' is an example of accidental being; 'Socrates is musical' means that the statement is 'true'; 'musical and just Coriscus' are 'accidentally one,' and so on. (15) He considers that not everything which appears, is true, and is surprised at his opponents' raising the question whether:

(14)

...those things are true which appear to the sleeping or to the waking. For obviously they do not think these to be open questions; no one, at least, if when he is in Libya he has fancied one night that he is in Athens, starts for the concert hall...(16)Further in Metaphysics, the Philosopher explains:

- That the 'one,' i.e. the measure or unit, is indivisible and not the same in all classes, that the 'measure is not always one number,' and that in every category we must 'ask what the one is, as we must ask what the existent is.'

...so that the first thing from which, as far as perception goes, nothing can be subtracted, all men make the measure, whether liquids or solids, whether of weight or of size, and they think they know the quantity when they know it by means of this measure. ... and in music [a 'one'] is the quarter-tone (because it is the least interval)...(17)

For here it is a quarter-tone, and there it is the vowel or the consonant; and there is another unit of weight and another of movement. But everywhere the one is indivisible either in quantity or in kind.(18)

But the measure is not always one in number--sometimes there are several; e.g. the quarter-tones (not to the ear, but as determined by the ratios) are two, and the articulate sounds by which we measure are more than one...(19)

And similarly if all existing things were tunes, they would have been a number, but a number of quarter-tones, and their essence would not have been number; and the one would have been something whose substance was not to be one but to be the quarter-tone.(20)- About 'the potent' in the sense of 'capable':

This sort of potency is found even in lifeless things, e.g. in instruments; for we say one lyre can speak, and another cannot speak at all, if it has not a good tone.(21)- That 'complete' has three meanings, a.o.:

That which in respect of excellence and goodness cannot be excelled in its kind; e.g. we have a complete doctor or a complete flute-player, when they lack nothing in respect of the form of their proper excellence.(22)- About what things can and cannot be 'mutilated,' he says that for something to be 'mutilated,' it must be a whole as well as divisible, and its essence must no longer be the same:

...to be mutilated, things must be such as in virtue of their essence have a certain position. Again, they must be continuous; for a musical scale consists of unlike parts and has position, but cannot become mutilated.(23)- Discussing 'prior' he considers 'actuality' prior to 'potency' both in formula (by being possible), 'substantiality', and 'time'--'one' actuality always precedes another in time right back to the actuality of the eternal prime mover':

This is why it is thought impossible to be...a harper if one has never played the harp; for he who learns to play the harp learns to play it by playing it, and all other learners do similarly.(24)- He cites the Pythagoreans who, because 'the attributes of numbers are present in a musical scale and in the heavens and in many other things,' supposed 'real things to be numbers--not separable numbers, however, but numbers of which real things consist.'(25)

- He cautions against believing that 'number' causes a thing to exist or that numerical analogies are anything more than pure coincidence.

But why need these numbers be causes? There are seven vowels, the scale consists of seven strings, ... at seven animals lose their teeth (at least some do, though some do not), ... These people are like the old-fashioned Homeric scholars, who see small resemblances but neglect great ones.

Some say ..., e.g. that the middle strings are represented by nine and eight, and that the epic verse has seventeen syllables, which is equal in number to the two strings,... And they say that the distance in the letters from alpha to omega is equal to that from the lowest note of the flute to the highest, and that the number of this note is equal to that of the whole choir in heaven. (26)In Nicomachean Ethics Aristotle asks what the good we are seeking can be? Here he notes that:

Since there are evidently more than one end, and we choose some of these (e.g. wealth, flutes, and in general instruments) for the sake of something else, clearly not all ends are final ends; but the chief good is evidently something final.(27)- Aristotle does not believe that happiness is the 'chief good' and seeks to give a clearer account of it and first looks to 'ascertain the function of man' and further determines that the function of man is 'activity of soul which follows or implies a rational principle,' and 'human good turns out to be activity of soul in accordance with virtue, and if there are more than one virtue, in accordance with the best and most complete':

For just as for a flute-player, a sculptor,or any artist, and, in general, for all things that have a function or activity, the good and the 'well' is thought to reside in the function, so would it seem to be for man, if he has a function.(28)

Now if the function of man is an activity of soul which follows or implies a rational principle, and if we say 'a so-and-so' and 'a good so-and-so' have a function which is the same in kind,e.g. a lyre-player and a good lyre-player, and so without qualification in all cases, eminence in respect of goodness being added to the name of the function (for the function of a lyre-player is to play the lyre, and that of a good lyre-player is to do so well): if this is the case,... human good turns out to be... (29)- In Book II Aristotle explains that 'the virtues we get by first exercising them, as also happens in the case of the arts as well', that 'from the same causes and by the same means every virtue is both produced and destroyed,' and that 'states of character arise out of like activities':

For the things we have to learn before we can do them, we learn by doing them, e.g. men become builders by building and lyre-players by playing the lyre; so too we become just by doing just acts, temperate by doing temperate acts, brave by doing brave acts.

...for it is from playing the lyre that both good and bad lyre-players are produced.

This is why the activities we exhibit must be of a certain kind; it is because the states of character correspond to the differences between these. It makes no small difference, then, whether we form habits of one kind or of another from our very youth; it makes a very great difference, or rather all the difference.(30)- In Book IX Aristotle considers friendships between dissimilars and the need for 'proportion that equalizes the parties and preserves the friendship.' In the political form of friendship, money is the common measure. Love of characters endures, whereas differences arise when one party gets something different and not what he or she desires:

...compare the story of the person who made promises to a lyre-player, promising him the more, the better he sang, but in the morning, when the other demanded the fulfilment of his promises, said that he had given pleasure for pleasure.(31)- In Book X the Philosopher explains that 'pleasures' differ in kind, intensify the activity they complete, and are hindered by the pleasures arising from other sources.

... for those derived from noble sources are different from those derived from base sources, and one cannot get the pleasure of the just man without being just, nor that of the musical man without being musical, and so on.(32)

...life is an activity, and each man is active about those things and with those faculties that he loves most; e.g. the musician is active with his hearing in reference to tunes, ...(33)

...e.g. it is those who enjoy geometrical thinking that become geometers and grasp the various propositions better, and, similarly, those who are fond of music or of building, and so on, make progress in their proper function by enjoying it...(34)

For people who are fond of playing the flute are incapable of attending to arguments if they overhear some one playing the flute...; so the pleasure connected with flute-playing destroys the activity concerned with argument.(35)One of the earliest surviving examples of notated Western music is the Second Delphic Hymn which is headed Paean (a lyric poem expressing triumph or thanksgiving) and Prosodion (a processional song) to the God. It was written two centuries later than Aristotle, in 128 BCE by Limenios, likely for performance at the Pythian Games in Delphi in 128 BCE. (36) It starts with a couple of instruments, a.o. the 'exciting' flute.

Let's now jump all the way to 1916 and discover Jan Hakan Aberg (1916 - 2012), first up in our list of 100-year anniversaries.

|

| Härnösand Cathedral (37) |

Aberg was a Swedish organist and composer active at Härnösand Cathedral.

He is represented in the current Swedish Book of Psalms (1986) with two songs, In dulci jubilo and Så älskade Gud världen all.

Here is an arrangement by Aberg of the psalm I himmelen, i himmelen (In Heav’n above) which was probably written in 1620 by Laurentius Laurinus. A serene start for the New Year.

_______________________________________________________________________________

(1) After Lysippos [CC BY-SA 2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons.

(2) David Binning Monro, "The Modes of Ancient Greek Music, I. Introductory." Oxford University, Clarendon Press, 1894, p. 1. (https://books.google.com/books?id=jmwpAAAAYAAJ&ots=bipnN551SQ&dq=greek%20modes%20and%20emotions&lr&pg=PA1#v=onepage&q=greek%20modes%20and%20emotions&f=false (01/09/2016))

(3) Golden, Leon. “Mimesis and Katharsis”. Classical Philology 64.3 (1969): 145–153. (http://www.jstor.org/stable/268156 (01/09/2016))

(4) Aristotle, "Politics."Politics, Book VIII, Chap. 5-7. (http://faculty.smu.edu/jkazez/mol09/AristotleOnMusic.htm (01/09/2016))

(5) For Aristotle's views on women, see here.

(6) Aristotle, "Prior Analytics." Bk. II: Ch. 27, 70b, 7, translation Richard McKeon, "The Basic Works of Aristotle," New York, Random House, 1941, p. 106.

(7) Aristotle, "Posterior Analytics." Bk. I: Ch. 24, 85a, 22, translation Richard McKeon, "The Basic Works of Aristotle," New York, Random House, 1941, p. 147. Coriscus was also a student of Plato and a lifelong friend of Aristotle. Whether all the attributes applied to Coriscus by Aristotle were true, is unsure.

(8) Aristotle, "Topics." Bk. I: Ch. 15, 106a-107b, translation Richard McKeon, "The Basic Works of Aristotle," New York, Random House, 1941, pp. 200-204.

(9) Aristotle, "Physics." Bk. I: Ch. 2, 185b, 32, translation Richard McKeon, "The Basic Works of Aristotle," New York, Random House, 1941, p. 221.

(10)Ib., Bk. I: Ch.5, 188a, 35, p. 227.

(11)Ib., Bk. IV: Ch.7, 214a, 7, p. 281.

(12)Ib., Bk. VII: Ch.4, 248b, 9, p. 349.

(13) Aristotle, "On the Soul." Bk. II: Ch. 8, 419b, 3, translation Richard McKeon, "The Basic Works of Aristotle," New York, Random House, 1941, pp. 570-573.

(14)Ib., Bk. III: Ch. 2, 426a, 27, pp. 583-584.

(15) Aristotle, "Metaphysics." Translation Richard McKeon, "The Basic Works of Aristotle," New York, Random House, 1941, p. 681.

(16) Aristotle, "Metaphysics." Bk. IV: Ch. 5, 1010b, 8, translation Richard McKeon, "The Basic Works of Aristotle," New York, Random House, 1941, p. 746.

(17)Ib., Bk. X: Ch. 1, 1053a, 13, p. 836.

(18)Ib., Bk. V: Ch. 6, 1016a, 18, p. 759.

(19)Ib., Bk. X: Ch. 1, 1053a, 14, p. 837. The numerical ratio here may be for example determined by 'string-length.'

(20)Ib., Bk. X: Ch. 2, 1053b, 34, p. 838.

(21)Ib., Bk. V: Ch. 12, 1019b, 13, p. 766.

(22)Ib., Bk. V: Ch. 16, 1021b, 13, p. 770.

(23)Ib., Bk. V: Ch. 27, 1024a, 11, p. 775.

(24)Ib., Bk. IX: Ch. 8, 1049b, 29, p. 829.

(25)Ib., Bk. XIV: Ch. 2, 1089b, 20, p. 918.

(26)Ib., Bk. XIV: Ch. 5, 1093a, 12, pp. 924-925.

(27) Aristotle, "Ethics." Bk. I: Ch. 7, 1097a, 24, translation Richard McKeon, "The Basic Works of Aristotle," New York, Random House, 1941, p. 941.

(28)Ib., Bk. I: Ch. 7, 1097b, 24, p. 942.

(29) Ib., Bk. I: Ch. 7, 1098a, 7, p. 943.

(30) Ib., Bk. II: Ch. 1, 1103a, 32, p. 952.

(31) Ib., Bk. IX: Ch. 1, 1164a, 15, p. 1077.

(32) Ib., Bk. X: Ch. 3, 1173b, 28, p. 1097.

(33) Ib., Bk. X: Ch. 4, 1175a, 10, p. 1100.

(34) Ib., Bk. X: Ch. 5, 1175a, 29, p. 1100.

(35) Ib., Bk. X: Ch. 5, 1175b, 1, p. 1100.

(36) The work was found by French archaeologists in 1893, inscribed on a wall of the Athenian Treasury building in Delphi.

(37) Henrik Sendelbach [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.